In 1996 I got punched in the face on the escalator of the 6 train at 51st St. As a woman rumbled past me, heading up the stairs she hooked my elbow – she turned and swung from above, with a closed fist covered with rings like brass knuckles. In an instant she cut the bridge of my nose and effectively tore up the delicate skin under my eyes. After threatening me with death if I retaliated, she continued her journey and my face dripped.

A year earlier I had quit my job as a museum preparator to become a freelancer. I worked for a UK based art shipping company, doing whatever needed doing for shipments to NY, mostly to the Lexington Avenue Armory for various art fairs. I worked every fair, and there were many as the art fair business was growing at that time. During some of the all-nighters I would stop and think about how I was the only woman in the building at 3:00 AM. I had already been art handling for 15 years, but the evolution of women doing that work still seemed somewhat fledgling. The union crew were a motley bunch of nappers behind walls, managers named Bruno and Steve, many generals of dubious intellect, all herded by a red-faced camel hair coated Irish guy named Doyle. They were a tribe of grunters and lifers. I would be yelled at regularly to be careful around the fork-lift as I unloaded delivered crates from trucks, and if I put my tools down, they would go away in seconds. The heavy lifting was not the crates, it was the navigation through the muddy brown misogynistic swamp, just trying to do my work. I rationalized it by thinking about how these fellows just did not know what to do with me, I was a vastly different species from the wives and daughters in Queens and New Jersey. Somehow this helped me-to think that the dismissive, sometimes abusive, and usually mean behavior had a tinge of fear of the unfamiliar in it. I admit the sabotage was challenging but would have been impossible had I not come from an upbringing of workers of both genders. Indeed, one of the sad days that year was when my father’s hammer disappeared, one that he used in his years in construction.

Back to the dripping face. I was on my way to the Armory that day to meet a truck. I called my husband to come meet me to help get me home, went to a deli for some ice, and headed into the Armory. The usual suspects were there, clumped around the big back door as usual. As I entered, I suddenly found myself surrounded by my nemeses. In a matter of minutes, the color of the world changed in the building. They clucked and prodded, all ready to call an ambulance, fan my brow, and do whatever they could do to help. I did not need a hospital – it was a matter of ice and aspirin as my injuries could not be stitched. But from those five minutes on life became tolerable when I was there. I had passed a test, earned a badge of honor, allowed them to be the white knights of their ancestry. My blood turned me into a damsel. It was not so much a shift in power, more like a new perception where my vulnerability was more understandable for them and they were no longer anxious about my presence in their midst. I freelanced there for another free and easy year until I was 3 months pregnant with our daughter, after which I took a break for a bit.

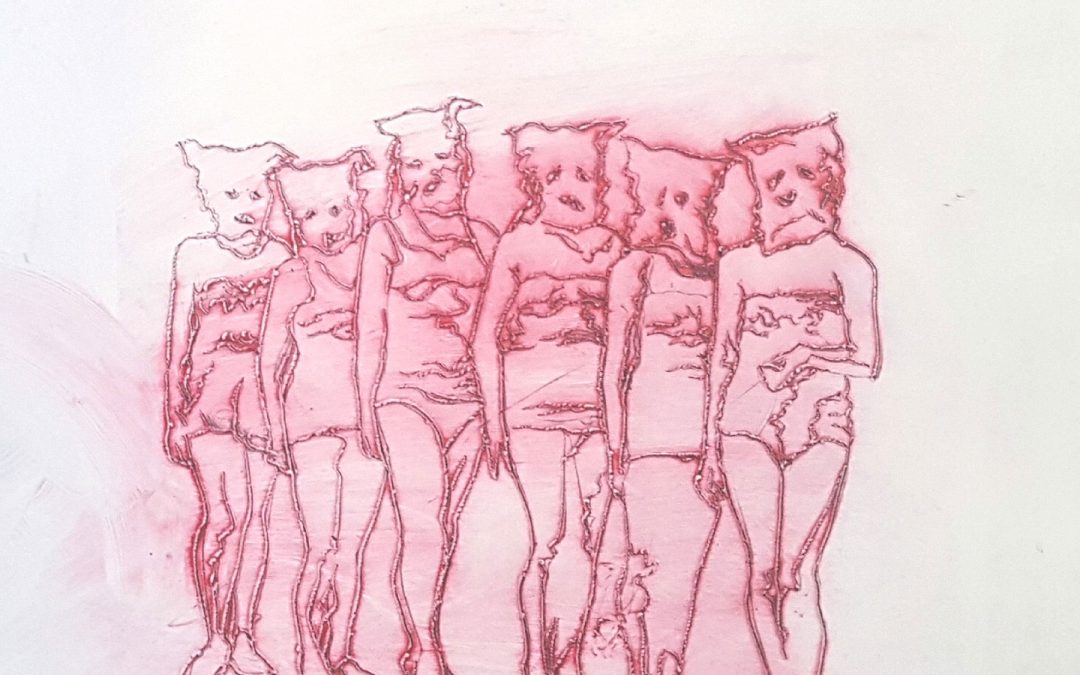

The work that I make has that day woven through it. The perception of others, the discrimination from which we operate and how we determine to use our strengths and weaknesses. In the post war years when gender norms were tipping back to “normal” beauty pageants were held with the women wearing hoods to cover faces to keep things simple. Upon discovery of these images I was horrified, and then fascinated. These images helped me to consider the generation of power and perception and I have continued to use the girls as a personal symbol. What we show to the world, and what we keep close is an equalizer. The critic Dan Kany once wrote that the works have a sort of unfocused power and violence, not unlike a smoking sawed-off shotgun. I received this comment with utmost pride, the fact that he got it – the power of what we keep and what we show, how we hold on, and when we let go. The subjectivity of beauty, its uses and its uselessness, the presence of our rage and desire, these are the elements of our currency and our history. And how we present these elements to the world is our own choice.

Twenty-five years later, to this day when I visit the Armory, Bruno and Steve and I pull out our wallets to show the updated pictures that we carry of our children who are now grown.